- Home

- P. G. Wodehouse

Ring For Jeeves Page 6

Ring For Jeeves Read online

Page 6

‘Is there a hope?’ he quavered, speaking rather like an invalid on a sickbed addressing his doctor.

‘I think so,’ said Monica.

‘I don’t,’ said Rory.

Monica quelled him with a glance.

‘The impression I got at that women’s lunch in New York,’ she said, ‘was that she was nibbling. I gave her quite a blast of propaganda and definitely softened her up. All that remains now is to administer the final shove. When she arrives, I’ll leave you alone together, so that you can exercise that well-known charm of yours. Give her the old personality.’

‘I will,’ said Bill fervently. ‘I’ll be like a turtle dove cooing to a female turtle-dove. I’ll play on her as on a stringed instrument.’

‘Well, mind you do, because if the sale comes off, I’m expecting a commission.’

‘You shall have it, Moke, old thing. You shall be repaid a thousandfold. In due season there will present themselves at your front door elephants laden with gold and camels bearing precious stones and rare spices.’

‘How about apes, ivory and peacocks?’

‘They’ll be there.’

Rory, the practical, hard-headed businessman, frowned on this visionary stuff.

‘Well, will they?’ he said. ‘The point seems to me extremely moot. Even on the assumption that this woman is weak in the head I can’t see her paying a fortune for a place like Rowcester Abbey. To start with, all the farms are gone.’

‘That’s true,’ said Bill, damped. ‘And the park belongs to the local golf club. There’s only the house and garden.’

‘The garden, yes. And we know all about the garden, don’t we? I was saying to Moke only a short while ago that whereas in the summer months the river is at the bottom of the garden—’

‘Oh, be quiet,’ said Monica. ‘I don’t see why you shouldn’t get fifteen thousand pounds, Bill. Maybe even as much as twenty.’

Bill revived like a watered flower.

‘Do you really think so?’

‘Of course she doesn’t,’ said Rory. ‘She’s just trying to cheer you up, and very sisterly of her, too. I honour her for it. Under that forbidding exterior there lurks a tender heart. But twenty thousand quid for a house from which even Reclaimed Juvenile Delinquents recoil in horror? Absurd. The thing’s a relic of the past. A hundred and forty-seven rooms!’

‘That’s a lot of house,’ argued Monica.

‘It’s a lot of junk,’ said Rory firmly. ‘It would cost a bally fortune to do it up.’

Monica was obliged to concede this.

‘I suppose so,’ she said. ‘Still, Mrs Spottsworth’s the sort of woman who would be quite prepared to spend a million or so on that. You’ve been making a few improvements, I notice,’ she said to Bill.

‘A drop in the bucket.’

‘You’ve even done something about the smell on the first-floor landing.’

‘Wish I had the money it cost.’

‘You’re hard up?’

‘Stony.’

‘Then where the dickens,’ said Rory, pouncing like a prosecuting counsel, ‘do all these butlers and housemaids come from? That girl Jill Stick-in-the-mud—’

‘Her name is not Stick-in-the-mud.’

Rory raised a restraining hand.

‘Her name may or may not be Stick-in-the-mud,’ he said, letting the point go, for after all it was a minor one, ‘but the fact remains that she was holding us spellbound just now with a description of your domestic amenities which suggested the mad luxury that led to the fall of Babylon. Platoons of butlers, beauty choruses of housemaids, cooks in reckless profusion and stories flying about of boys to clean the knives and boots. … I said to Moke after she’d left that I wondered if you had set up as a gentleman bur… That reminds me, old girl. Did you tell Bill about the police?’

Bill leaped a foot, and came down shaking in every limb.

‘The police? What about the police?’

‘Some blighter rang up from the local gendarmerie. The rozzers want to question you.’

‘What do you mean, question me?’

‘Grill you,’ explained Rory. ‘Give you the third degree. And there was another call before that. A mystery man who didn’t give his name. He and Moke kidded back and forth for a while.’

‘Yes, I talked to him,’ said Monica. ‘He had a voice that sounded as if he ate spinach with sand in it. He was inquiring about the licence number of your car.’

‘What!’

‘You haven’t run into somebody’s cow, have you? I understand that’s a very serious offence nowadays.’

Bill was still quivering briskly.

‘You mean someone was wanting to know the licence number of my car?’

‘That’s what I said. Why, what’s the matter, Bill? You’re looking as worried as a prune.’

‘White and shaken,’ agreed Rory. ‘Like a side-car.’ He laid a kindly hand on his brother-in-law’s shoulder. ‘Bill, tell me. Be frank. Why are you wanted by the police?’

‘I’m not wanted by the police.’

‘Well, it seems to be their dearest wish to get their hands on you. One theory that crossed my mind,’ said Rory, ‘was—I mentioned it to you, Moke, if you remember—that you had found some opulent bird with a guilty secret and were going in for a spot of blackmail. This may or may not be the case, but if it is, now is the time to tell us, Bill, old man. You’re among friends. Moke’s broad-minded, and I’m broad-minded. I know the police look a bit squiggle-eyed at blackmail, but I can’t see any objection to it myself. Quick profits and practically no overheads. If I had a son, I’m not at all sure I wouldn’t have him trained for that profession. So if the flatties are after you and you would like a helping hand to get you out of the country before they start watching the ports, say the word, and we’ll…’

‘Mrs Spottsworth,’ announced Jeeves from the doorway, and a moment later Bill had done another of those leaps in the air which had become so frequent with him of late.

He stood staring pallidly at the vision that entered.

Chapter 7

Mrs Spottsworth had come sailing into the room with the confident air of a woman who knows that her hat is right, her dress is right, her shoes are right and her stockings are right and that she has a matter of forty-two million dollars tucked away in sound securities, and Bill, with a derelict country house for sale, should have found her an encouraging spectacle. For unquestionably she looked just the sort of person who would buy derelict English country houses by the gross without giving the things a second thought.

But his mind was not on business transactions. It had flitted back a few years and was in the French Riviera, where he and this woman had met and—he could not disguise it from himself—become extremely matey.

It had all been perfectly innocent, of course—just a few moonlight drives, one or two mixed bathings and hob-nobbings at Eden Roc and the ordinary exchanges of civilities customary on the French Riviera—but it seemed to him that there was a grave danger of her introducing into their relations now that touch of Auld Lang Syne which is the last thing a young man wants when he has a fiancée around—and a fiancée, moreover, who has already given evidence of entertaining distressing suspicions.

Mrs Spottsworth had come upon him as a complete and painful surprise. At Cannes he had got the impression that her name was Bessemer, but of course in places like Cannes you don’t bother much about surnames. He had, he recalled, always addressed her as Rosie, and she—he shuddered—had addressed him as Billiken. A clear, but unpleasant, picture rose before his eyes of Jill’s face when she heard her addressing him as Billiken at dinner tonight. Most unfortunately, through some oversight, he had omitted to mention to Jill his Riviera acquaintance Mrs Bessemer, and he could see that she might conceivably take a little explaining away.

‘How nice to see you again, Rosalinda,’ said Monica. ‘So glad you found your way here all right. It’s rather tricky after you leave the main road. My husband, Sir Roderic

k Carmoyle. And this is—’

‘Billiken!’ cried Mrs Spottsworth, with all the enthusiasm of a generous nature. It was plain that if the ecstasy occasioned by this unexpected encounter was a little one-sided, on her side at least it existed in full measure.

‘Eh?’ said Monica.

‘Mr Belfry and I are old friends. We knew each other in Cannes a few years ago, when I was Mrs Bessemer.’

‘Bessemer!’

‘It was not long after my husband had passed the veil owing to having a head-on collision with a truck full of beer bottles on the Jericho Turnpike. His name was Clifton Bessemer.’

Monica shot a pleased and congratulatory look at Bill. She knew all about Mrs Bessemer of Cannes. She was aware that her brother had given this Mrs Bessemer the rush of a lifetime, and what better foundation could a young man with a house to sell have on which to build?

‘Well, that’s fine,’ she said. ‘You’ll have all sorts of things to talk about, won’t you? But he isn’t Mr Belfry now, he’s Lord Rowcester.’

‘Changed his name,’ explained Rory. ‘The police are after him, and an alias was essential.’

‘Oh, don’t be an ass, Rory. He came into the title,’ said Monica. ‘You know how it is in England. You start out as something, and then someone dies and you do a switch. Our uncle, Lord Rowcester, pegged out not long ago, and Bill was his heir, so he shed the Belfry and took on the Rowcester.’

‘I see. Well, to me he will always be Billiken. How are you, Billiken?’

Bill found speech, though not much of it and what there was rather rasping.

‘I’m fine, thanks—er—Rosie.’

‘Rosie?’ said Rory, startled and, like the child of nature he was, making no attempt to conceal his surprise. ‘Did I hear you say Rosie?’

Bill gave him a cold look.

‘Mrs Spottsworth’s name, as you have already learned from a usually well-informed source—viz. Moke—is Rosalinda. All her friends—even casual acquaintances like myself—called her Rosie.’

‘Oh, ah,’ said Rory. ‘Quite, quite. Very natural, of course.’

‘Casual acquaintances?’ said Mrs Spottsworth, pained.

Bill plucked at his tie.

‘Well, I mean blokes who just knew you from meeting you at Cannes and so forth.’

‘Cannes!’ cried Mrs Spottsworth ecstatically. ‘Dear, sunny, gay, delightful Cannes! What times we had there, Billiken! Do you remember—’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Bill. ‘Very jolly, the whole thing. Won’t you have a drink or a sandwich or a cigar or something?’

Fervently he blessed the Mainwarings’ Peke for being so confirmed a hypochondriac that it had taken Jill away to the other side of the county. By the time she returned, Mrs Spottsworth, he trusted, would have simmered down and become less expansive on the subject of the dear old days. He addressed himself to the task of curbing her exuberance.

‘Nice to welcome you to Rowcester Abbey,’ he said formally.

‘Yes, I hope you’ll like it,’ said Monica.

‘It’s the most wonderful place I ever saw!’

‘Would you say that? Mouldering old ruin, I’d call it,’ said Rory judicially, and was fortunate enough not to catch his wife’s eye. ‘Been decaying for centuries. I’ll bet if you shook those curtains, a couple of bats would fly out.’

‘The patina of Time!’ said Mrs Spottsworth. ‘I adore it.’ She closed her eyes. ‘“The dead, twelve deep, clutch at you as you go by,”’ she murmured.

‘What a beastly idea,’ said Rory. ‘Even a couple of clutching corpses would be a bit over the odds, in my opinion.’

Mrs Spottsworth opened her eyes. She smiled.

‘I’m going to tell you something very strange,’ she said. ‘It struck me so strongly when I came in at the front door I had to sit down for a moment. Your butler thought I was ill.’

‘You aren’t, I hope?’

‘No, not at all. It was simply that I was… overcome. I realised that I had been here before.’

Monica looked politely puzzled. It was left to Rory to supply the explanation.

‘Oh, as a sightseer?’ he said. ‘One of the crowd that used to come on Fridays during the summer months to be shown over the place at a bob a head. I remember them well in the days when you and I were walking out, Moke. The Gogglers, we used to call them. They came in charabancs and dropped nut chocolate on the carpets. Not that dropping nut chocolate on them would make these carpets any worse. That’s all been discontinued now, hasn’t it, Bill? Nothing left to goggle at, I suppose. The late Lord Rowcester,’ he explained to the visitor, ‘stuck the Americans with all his best stuff, and now there’s not a thing in the place worth looking at. I was saying to my wife only a short while ago that by far the best policy in dealing with Rowcester Abbey would be to burn it down.’

A faint moan escaped Monica. She raised her eyes heavenwards, as if pleading for a thunderbolt to strike this man. If this was her Roderick’s idea of selling goods to a customer, it seemed a miracle that he had ever managed to get rid of a single hose-pipe, lawnmower or bird-bath.

Mrs Spottsworth shook her head with an indulgent smile.

‘No, no, I didn’t mean that I had been here in my present corporeal envelope. I meant in a previous incarnation. I’m a Rotationist, you know.’

Rory nodded intelligently.

‘Ah, yes. Elks, Shriners and all that. I’ve seen pictures of them, in funny hats.’

‘No, no, you are thinking of Rotarians. I am a Rotationist, which is quite different. We believe that we are reborn as one of our ancestors every ninth generation.’

‘Ninth?’ said Monica, and began to count on her fingers.

‘The mystic ninth house. Of course you’ve read the Zend Avesta of Zoroaster, Sir Roderick?’

‘I’m afraid not. Is it good?’

‘Essential, I would say.’

‘I’ll put it on my library list,’ said Rory. ‘By Agatha Christie, isn’t it?’

Monica had completed her calculations.

‘Ninth… That seems to make me Lady Barbara, the leading hussy of Charles II’s reign.’

Mrs Spottsworth was impressed.

‘I suppose I ought to be calling you Lady Barbara and asking you about your latest love affair.’

‘I only wish I could remember it. From what I’ve heard of her, it would make quite a story.’

‘Did she get herself sunburned all over?’ asked Rory. ‘Or was she more of an indoor girl?’

Mrs Spottsworth had closed her eyes again.

‘I feel influences,’ she said. ‘I even hear faint whisperings. How strange it is, coming into a house that you last visited three hundred years ago. Think of all the lives that have been lived within these ancient walls. And they are here, all around us, creating an intriguing aura for this delicious old house.’

Monica caught Bill’s eye.

‘It’s in the bag, Bill,’ she whispered.

‘Eh?’ said Rory in a loud, hearty voice. ‘What’s in the bag?’

‘Oh, shut up.’

‘But what is in the… Ouch!’ He rubbed a well-kicked ankle. ‘Oh, ah, yes, of course. Yes, I see what you mean.’

Mrs Spottsworth passed a hand across her brow. She appeared to be in a sort of mediumistic trance.

‘I seem to remember a chapel. There is a chapel here?’

‘Ruined,’ said Monica.

‘You don’t need to tell her that, old girl,’ said Rory.

‘I knew it. And there’s a Long Gallery.’

‘That’s right,’ said Monica. ‘A duel was fought in it in the eighteenth century. You can still see the bullet holes in the walls.’

‘And dark stains on the floor, no doubt. This place must be full of ghosts.’

This, felt Monica, was an idea to be discouraged at the outset.

‘Oh, no, don’t worry,’ she said heartily. ‘Nothing like that in Rowcester Abbey,’ and was surprised to observe that her guest was gazing at her

with large, woebegone eyes like a child informed that the evening meal will not be topped off with ice-cream.

‘But I want ghosts,’ said Mrs Spottsworth. ‘I must have ghosts. Don’t tell me there aren’t any?’

Rory was his usual helpful self.

‘There’s what we call the haunted lavatory on the ground floor,’ he said. ‘Every now and then, when there’s nobody near it, the toilet will suddenly flush, and when a death is expected in the family, it just keeps going and going. But we don’t know if it’s a spectre or just a defect in the plumbing.’

‘Probably a poltergeist,’ said Mrs Spottsworth, seeming a little disappointed. ‘But are there no visual manifestations?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Don’t be silly, Rory,’ said Monica. ‘Lady Agatha.’

Mrs Spottsworth was intrigued.

‘Who was Lady Agatha?’

‘The wife of Sir Caradoc the Crusader. She has been seen several times in the ruined chapel.’

‘Fascinating, fascinating,’ said Mrs Spottsworth. ‘And now let me take you to the Long Gallery. Don’t tell me where it is. Let me see if I can’t find it for myself.’

She closed her eyes, pressed her fingertips to her temples, paused for a moment, opened her eyes and started off. As she reached the door, Jeeves appeared.

‘Pardon me, m’lord.’

‘Yes, Jeeves?’

‘With reference to Mrs Spottsworth’s dog, m’lord, I would appreciate instructions as to meal hours and diet.’

‘Pomona is very catholic in her tastes,’ said Mrs Spottsworth. ‘She usually dines at five, but she is not at all fussy.’

‘Thank you, madam.’

‘And now I must concentrate. This is a test.’ Mrs Spottsworth applied her fingertips to her temple once more. ‘Follow, please, Monica. You, too, Billiken. I am going to take you straight to the Long Gallery.’

Jill the Reckless

Jill the Reckless Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Uncle Fred in the Springtime Sunset at Blandings

Sunset at Blandings Uneasy Money

Uneasy Money The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion

The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion Right Ho, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves The Intrusion of Jimmy

The Intrusion of Jimmy The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1:

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: Aunts Aren't Gentlemen:

Aunts Aren't Gentlemen: The Luck of the Bodkins

The Luck of the Bodkins The Little Nugget

The Little Nugget Money for Nothing

Money for Nothing Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin Mulliner Nights

Mulliner Nights Blandings Castle and Elsewhere

Blandings Castle and Elsewhere Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens Carry On, Jeeves!

Carry On, Jeeves! The Little Warrior

The Little Warrior Ice in the Bedroom

Ice in the Bedroom Leave It to Psmith

Leave It to Psmith Thank You, Jeeves:

Thank You, Jeeves: Money in the Bank

Money in the Bank The Man Upstairs and Other Stories

The Man Upstairs and Other Stories Galahad at Blandings

Galahad at Blandings The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5 Uncle Dynamite

Uncle Dynamite Mike at Wrykyn

Mike at Wrykyn Something Fresh

Something Fresh Eggs, Beans and Crumpets

Eggs, Beans and Crumpets The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books)

The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books) Blanding Castle Omnibus

Blanding Castle Omnibus Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology

Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology Mr. Mulliner Speaking

Mr. Mulliner Speaking Hot Water

Hot Water The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves The Mating Season

The Mating Season Meet Mr. Mulliner

Meet Mr. Mulliner The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories

The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel

Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel Young Men in Spats

Young Men in Spats The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4 A Pelican at Blandings:

A Pelican at Blandings: Plum Pie

Plum Pie Wodehouse On Crime

Wodehouse On Crime The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves The Man With Two Left Feet

The Man With Two Left Feet Full Moon:

Full Moon: Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit:

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit: Ring For Jeeves

Ring For Jeeves Something New

Something New The Girl on the Boat

The Girl on the Boat The Girl in Blue

The Girl in Blue Pigs Have Wings:

Pigs Have Wings: The Adventures of Sally

The Adventures of Sally A Prefect's Uncle

A Prefect's Uncle Lord Emsworth and Others

Lord Emsworth and Others Quick Service

Quick Service The Prince and Betty

The Prince and Betty The Gem Collector

The Gem Collector The Gold Bat

The Gold Bat Expecting Jeeves

Expecting Jeeves Doctor Sally

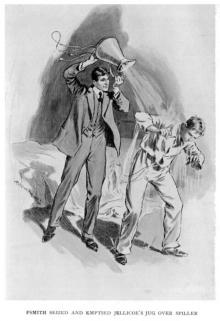

Doctor Sally Psmith, Journalist

Psmith, Journalist The Golf Omnibus

The Golf Omnibus Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather A Damsel in Distress

A Damsel in Distress The Coming of Bill

The Coming of Bill Summer Lightning

Summer Lightning Piccadilly Jim

Piccadilly Jim Psmith in the City

Psmith in the City The Pothunters

The Pothunters Service With a Smile

Service With a Smile Big Money

Big Money Three Men and a Maid

Three Men and a Maid Mike and Psmith

Mike and Psmith Mike

Mike Tales of St. Austin's

Tales of St. Austin's Indiscretions of Archie

Indiscretions of Archie Pigs Have Wings

Pigs Have Wings The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4 The White Feather

The White Feather Luck of the Bodkins

Luck of the Bodkins THE SPRING SUIT

THE SPRING SUIT Full Moon

Full Moon Very Good, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves Thank You, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves Reginald's Record Knock.

Reginald's Record Knock. Wodehouse At the Wicket

Wodehouse At the Wicket LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster)

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster) The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1 Jeeves in the offing jaw-12

Jeeves in the offing jaw-12