- Home

- P. G. Wodehouse

Leave It to Psmith

Leave It to Psmith Read online

Table of Contents

Cover

Copyright

About the Author

Also by P.G. Wodehouse

Leave it to Psmith

Contents

1 DARK PLOTTINGS AT BLANDINGS CASTLE

2 ENTER PSMITH

3 EVE BORROWS AN UMBRELLA

4 PAINFUL SCENE AT THE DRONES CLUB

5 PSMITH APPLIES FOR EMPLOYMENT

6 LORD EMSWORTH MEETS A POET

7 BAXTER SUSPECTS

8 CONFIDENCES ON THE LAKE

9 PSMITH ENGAGES A VALET

10 SENSATIONAL OCCURRENCE AT A POETRY READING

11 ALMOST ENTIRELY ABOUT FLOWER-POTS

12 MORE ON THE FLOWER-POT THEME

13 PSMITH RECEIVES GUESTS

14 PSMITH ACCEPTS EMPLOYMENT

Other Books by P.G. Wodehouse

Also Available in Arrow

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781409064497

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Arrow Books 2008

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright by The Trustees of the Wodehouse Estate

All rights reserved

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in the United Kingdom in 1923 by Herbert Jenkins Ltd

Arrow BooksThe Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

www.rbooks.co.uk

www.wodehouse.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099513797

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found atwww.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Typeset by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, EssexPrinted and bound in the United Kingdom by

CPI Bookmarque, Croydon, CR0 4TD

The author of almost a hundred books and the creator of Jeeves, Blandings Castle, Psmith, Ukridge, Uncle Fred and Mr Mulliner, P.G. Wodehouse was born in 1881 and educated at Dulwich College. After two years with the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank he became a full-time writer, contributing to a variety of periodicals including Punch and the Globe. He married in 1914. As well as his novels and short stories, he wrote lyrics for musical comedies with Guy Bolton and Jerome Kern, and at one time had five musicals running simultaneously on Broadway. His time in Hollywood also provided much source material for fiction.

At the age of 93, in the New Year’s Honours List of 1975, he received a long-overdue knighthood, only to die on St Valentine’s Day some 45 days later.

To

MY DAUGHTER LEONORA

Queen of her species.

Some of the P.G. Wodehouse titles to be published by Arrow in 2008

JEEVES

The Inimitable Jeeves

Carry On, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves

The Code of the Woosters

Joy in the Morning

The Mating Season

Ring for Jeeves

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit

Jeeves in the Offing

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves

Much Obliged, Jeeves

Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen

BLANDINGS

Something Fresh

Leave it to Psmith

Summer Lightning

Blandings Castle

Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Full Moon

Pigs Have Wings

Service with a Smile

A Pelican at Blandings

MULLINER

Meet Mr Mulliner

Mulliner Nights

Mr Mulliner Speaking

UNCLE FRED

Cocktail Time

Uncle Dynamite

GOLF

The Clicking of Cuthbert

The Heart of a Goof

OTHERS

Piccadilly Jim

Ukridge

The Luck of the Bodkins

Laughing Gas

A Damsel in Distress

The Small Bachelor

Hot Water

Summer Moonshine

The Adventures of Sally

Money for Nothing

The Girl in Blue

Big Money

CONTENTS

1 DARK PLOTTINGS AT BLANDINGS CASTLE

2 ENTER PSMITH

3 EVE BORROWS AN UMBRELLA

4 PAINFUL SCENE AT THE DRONES CLUB

5 PSMITH APPLIES FOR EMPLOYMENT

6 LORD EMSWORTH MEETS A POET

7 BAXTER SUSPECTS

8 CONFIDENCES ON THE LAKE

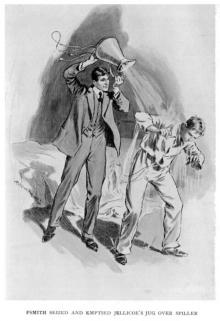

9 PSMITH ENGAGES A VALET

10 SENSATIONAL OCCURRENCE AT A POETRY READING

11 ALMOST ENTIRELY ABOUT FLOWER-POTS

12 MORE ON THE FLOWER-POT THEME

13 PSMITH RECEIVES GUESTS

14 PSMITH ACCEPTS EMPLOYMENT

1 DARK PLOTTINGS AT BLANDINGS CASTLE

§ 1

AT the open window of the great library of Blandings Castle, drooping like a wet sock, as was his habit when he had nothing to prop his spine against, the Earl of Emsworth, that amiable and boneheaded peer, stood gazing out over his domain.

It was a lovely morning and the air was fragrant with gentle summer scents. Yet in his lordship’s pale blue eyes there was a look of melancholy. His brow was furrowed, his mouth peevish. And this was all the more strange in that he was normally as happy as only a fluffy-minded man with excellent health and a large income can be. A writer, describing Blandings Castle in a magazine article, had once said: ‘Tiny mosses have grown in the cavities of the stones, until, viewed near at hand, the place seems shaggy with vegetation.’ It would not have been a bad description of the proprietor. Fifty-odd years of serene and unruffled placidity had given Lord Emsworth a curiously moss-covered look. Very few things had the power to disturb him. Even his younger son, the Hon. Freddie Threepwood, could only do it occasionally.

Yet now he was sad. And – not to make a mystery of it any longer – the reason of his sorrow was the fact that he had mislaid his glasses and without them was as blind, to use his own neat simile, as abat. He was keenly aware of the sunshine that poured down on his gardens, and was yearning to pop out and potter among the flowers he loved. But no man, pop he never so wisely, can hope to potter with any good result if the world is a mere blur.

The door behind him opened, and Beach the butler entered, a dignified procession of one.

‘Who’s that?’ inquired Lord Emsworth, spinning on his axis.

‘It is I, your lordship – Beach.’

‘Have you found th

em?’

‘Not yet, your lordship,’ sighed the butler.

‘You can’t have looked.’

‘I have searched assiduously, your lordship, but without avail. Thomas and Charles also announce non-success. Stokes has not yet made his report.’

‘Ah!’

‘I am re-despatching Thomas and Charles to your lordship’s bedroom,’ said the Master of the Hunt. ‘I trust that their efforts will be rewarded.’

Beach withdrew, and Lord Emsworth turned to the window again. The scene that spread itself beneath him – though he was unfortunately not able to see it – was a singularly beautiful one, for the castle, which is one of the oldest inhabited houses in England, stands upon a knoll of rising ground at the southern end of the celebrated Vale of Blandings in the county of Shropshire. Away in the blue distance wooded hills ran down to where the Severn gleamed like an unsheathed sword; while up from the river rolling park-land, mounting and dipping, surged in a green wave almost to the castle walls, breaking on the terraces in a many-coloured flurry of flowers as it reached the spot where the province of Angus McAllister, his lordship’s head gardener, began. The day being June the thirtieth, which is the very high-tide time of summer flowers, the immediate neighbourhood of the castle was ablaze with roses, pinks, pansies, carnations, hollyhocks, columbines, larkspurs, London pride, Canterbury bells, and a multitude of other choice blooms of which only Angus could have told you the names. A conscientious man was Angus; and in spite of being a good deal hampered by Lord Emsworth’s amateur assistance, he showed excellent results in his department. In his beds there was much at which to point with pride, little to view with concern.

Scarcely had Beach removed himself when Lord Emsworth was called upon to turn again. The door had opened for the second time, and a young man in a beautifully-cut suit of grey flannel was standing in the doorway. He had a long and vacant face topped by shining hair brushed back and heavily brillian-tined after the prevailing mode, and he was standing on one leg. For Freddie Threepwood was seldom completely at his ease in his parent’s presence.

‘Hallo, guv’nor.’

‘Well, Frederick?’

It would be paltering with the truth to say that Lord Emsworth’s greeting was a warm one. It lacked the note of true affection. A few weeks before he had had to pay a matter of five hundred pounds to settle certain racing debts for his offspring; and, while this had not actually dealt an irretrievable blow at his bank account, it had undeniably tended to diminish Freddie’s charm in his eyes.

‘Hear you’ve lost your glasses, guv’nor.’

‘That is so.’

‘Nuisance, what?’

‘Undeniably.’

‘Ought to have a spare pair.’

‘I have broken my spare pair.’

‘Tough luck! And lost the other?’

‘And, as you say, lost the other.’

‘Have you looked for the bally things?’

‘I have.’

‘Must be somewhere, I mean.’

‘Quite possibly.’

‘Where,’ asked Freddie, warming to his work, ‘did you see them last?’

‘Go away!’ said Lord Emsworth, on whom his child’s conversation had begun to exercise an oppressive effect.

‘Eh?’

‘Go away!’

‘Go away?’

‘Yes, go away!’

‘Right ho!’

The door closed. His lordship returned to the window once more.

He had been standing there some few minutes when one of those miracles occurred which happen in libraries. Without sound or warning a section of books started to move away from the parent body and, swinging out in a solid chunk into the room, showed a glimpse of a small, study-like apartment. A young man in spectacles came noiselessly through and the books returned to their place.

The contrast between Lord Emsworth and the new-comer, as they stood there, was striking, almost dramatic. Lord Emsworth was so acutely spectacle-less; Rupert Baxter, his secretary, so pronouncedly spectacled. It was his spectacles that struck you first as you saw the man. They gleamed efficiently at you. If you had a guilty conscience, they pierced you through and through; and even if your conscience was one hundred per cent. pure you could not ignore them. ‘Here,’ you said to yourself, ‘is an efficient young man in spectacles.’

In describing Rupert Baxter as efficient, you did not overestimate him. He was essentially that. Technically but a salaried subordinate, he had become by degrees, owing to the limp amiability of his employer, the real master of the house. He was the Brains of Blandings, the man at the switch, the person in charge, and the pilot, so to speak, who weathered the storm. Lord Emsworth left everything to Baxter, only asking to be allowed to potter in peace; and Baxter, more than equal to the task, shouldered it without wincing.

Having got within range, Baxter coughed; and Lord Emsworth, recognising the sound, wheeled round with a faint flicker of hope. It might be that even this apparently insoluble problem of the missing pince-nez would yield before the other’s efficiency.

‘Baxter, my dear fellow, I’ve lost my glasses. My glasses. I have mislaid them. I cannot think where they can have gone to. You haven’t seen them anywhere by any chance?’

‘Yes, Lord Emsworth,’ replied the secretary, quietly equal to the crisis. ‘They are hanging down your back.’

‘Down my back? Why, bless my soul!’ His lordship tested the statement and found it – like all Baxter’s statements – accurate. ‘Why, bless my soul, so they are! Do you know, Baxter, I really believe I must be growing absent-minded.’ He hauled in the slack, secured the pince-nez, adjusted them beamingly. His irritability had vanished like the dew off one of his roses. ‘Thank you, Baxter, thank you. You are invaluable.’

And with a radiant smile Lord Emsworth made buoyantly for the door, en route for God’s air and the society of McAllister. The movement drew from Baxter another cough – a sharp, peremptory cough this time; and his lordship paused, reluctantly, like a dog whistled back from the chase. A cloud fell over the sunniness of his mood. Admirable as Baxter was in so many respects, he had a tendency to worry him at times; and something told Lord Emsworth that he was going to worry him now.

‘The car will be at the door,’ said Baxter with quiet firmness, ‘at two sharp.’

‘Car? What car?’

‘The car to take you to the station.’

‘Station? What station?’

Rupert Baxter preserved his calm. There were times when he found his employer a little trying, but he never showed it.

‘You have perhaps forgotten, Lord Emsworth, that you arranged with Lady Constance to go to London this afternoon.’

‘Go to London!’ gasped Lord Emsworth, appalled. ‘In weather like this? With a thousand things to attend to in the garden? What a perfectly preposterous notion! Why should I go to London? I hate London.’

‘You arranged with Lady Constance that you would give Mr McTodd lunch to-morrow at your club.’

‘Who the devil is Mr McTodd?’

‘The well-known Canadian poet.’

‘Never heard of him.’

‘Lady Constance has long been a great admirer of his work. She wrote inviting him, should he ever come to England, to pay a visit to Blandings. He is now in London and is to come down to-morrow for two weeks. Lady Constance’s suggestion was that, as a compliment to Mr McTodd’s eminence in the world of literature, you should meet him in London and bring him back here yourself.’

Lord Emsworth remembered now. He also remembered that this positively infernal scheme had not been his sister Constance’s in the first place. It was Baxter who had made the suggestion, and Constance had approved. He made use of the recovered pince-nez to glower through them at his secretary; and not for the first time in recent months was aware of a feeling that this fellow Baxter was becoming a dashed infliction. Baxter was getting above himself, throwing his weight about, making himself a confounded nuisance. He wished he could ge

t rid of the man. But where could he find an adequate successor? That was the trouble. With all his drawbacks, Baxter was efficient. Nevertheless, for a moment Lord Emsworth toyed with the pleasant dream of dismissing him. And it is possible, such was his exasperation, that he might on this occasion have done something practical in that direction, had not the library door at this moment opened for the third time, to admit yet another intruder – at the sight of whom his lordship’s militant mood faded weakly.

‘Oh – hallo, Connie!’ he said, guiltily, like a small boy caught in the jam cupboard. Somehow his sister always had this effect upon him.

Of all those who had entered the library that morning the new arrival was the best worth looking at. Lord Emsworth was tall and lean and scraggy, Rupert Baxter thick-set and handicapped by that vaguely grubby appearance which is presented by swarthy young men of bad complexion, and even Beach, though dignified, and Freddie, though slim, would never have got far in a beauty competition. But Lady Constance Keeble really took the eye. She was a strikingly handsome woman in the middle forties. She had a fair, broad brow, teeth of a perfect even whiteness, and the carriage of an empress. Her eyes were large and grey, and gentle – and incidentally misleading, for gentle was hardly the adjective which anybody who knew her would have applied to Lady Constance. Though genial enough when she got her way, on the rare occasions when people attempted to thwart her she was apt to comport herself in a manner reminiscent of Cleopatra on one of the latter’s bad mornings.

‘I hope I am not disturbing you,’ said Lady Constance with a bright smile. ‘I just came in to tell you to be sure not to forget, Clarence, that you are going to London this afternoon to meet Mr McTodd.’

‘I was just telling Lord Emsworth,’ said Baxter, ‘that the car would be at the door at two.’

‘Thank you, Mr Baxter. Of course I might have known that you would not forget. You are so wonderfully capable. I don’t know what in the world we would do without you.’

The Efficient Baxter bowed. But, though gratified, he was not overwhelmed by the tribute. The same thought had often occurred to him independently.

‘If you will excuse me,’ he said, ‘I have one or two things to attend to . . .’

Jill the Reckless

Jill the Reckless Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Uncle Fred in the Springtime Sunset at Blandings

Sunset at Blandings Uneasy Money

Uneasy Money The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion

The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion Right Ho, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves The Intrusion of Jimmy

The Intrusion of Jimmy The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1:

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: Aunts Aren't Gentlemen:

Aunts Aren't Gentlemen: The Luck of the Bodkins

The Luck of the Bodkins The Little Nugget

The Little Nugget Money for Nothing

Money for Nothing Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin Mulliner Nights

Mulliner Nights Blandings Castle and Elsewhere

Blandings Castle and Elsewhere Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens Carry On, Jeeves!

Carry On, Jeeves! The Little Warrior

The Little Warrior Ice in the Bedroom

Ice in the Bedroom Leave It to Psmith

Leave It to Psmith Thank You, Jeeves:

Thank You, Jeeves: Money in the Bank

Money in the Bank The Man Upstairs and Other Stories

The Man Upstairs and Other Stories Galahad at Blandings

Galahad at Blandings The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5 Uncle Dynamite

Uncle Dynamite Mike at Wrykyn

Mike at Wrykyn Something Fresh

Something Fresh Eggs, Beans and Crumpets

Eggs, Beans and Crumpets The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books)

The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books) Blanding Castle Omnibus

Blanding Castle Omnibus Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology

Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology Mr. Mulliner Speaking

Mr. Mulliner Speaking Hot Water

Hot Water The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves The Mating Season

The Mating Season Meet Mr. Mulliner

Meet Mr. Mulliner The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories

The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel

Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel Young Men in Spats

Young Men in Spats The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4 A Pelican at Blandings:

A Pelican at Blandings: Plum Pie

Plum Pie Wodehouse On Crime

Wodehouse On Crime The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves The Man With Two Left Feet

The Man With Two Left Feet Full Moon:

Full Moon: Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit:

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit: Ring For Jeeves

Ring For Jeeves Something New

Something New The Girl on the Boat

The Girl on the Boat The Girl in Blue

The Girl in Blue Pigs Have Wings:

Pigs Have Wings: The Adventures of Sally

The Adventures of Sally A Prefect's Uncle

A Prefect's Uncle Lord Emsworth and Others

Lord Emsworth and Others Quick Service

Quick Service The Prince and Betty

The Prince and Betty The Gem Collector

The Gem Collector The Gold Bat

The Gold Bat Expecting Jeeves

Expecting Jeeves Doctor Sally

Doctor Sally Psmith, Journalist

Psmith, Journalist The Golf Omnibus

The Golf Omnibus Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather A Damsel in Distress

A Damsel in Distress The Coming of Bill

The Coming of Bill Summer Lightning

Summer Lightning Piccadilly Jim

Piccadilly Jim Psmith in the City

Psmith in the City The Pothunters

The Pothunters Service With a Smile

Service With a Smile Big Money

Big Money Three Men and a Maid

Three Men and a Maid Mike and Psmith

Mike and Psmith Mike

Mike Tales of St. Austin's

Tales of St. Austin's Indiscretions of Archie

Indiscretions of Archie Pigs Have Wings

Pigs Have Wings The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4 The White Feather

The White Feather Luck of the Bodkins

Luck of the Bodkins THE SPRING SUIT

THE SPRING SUIT Full Moon

Full Moon Very Good, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves Thank You, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves Reginald's Record Knock.

Reginald's Record Knock. Wodehouse At the Wicket

Wodehouse At the Wicket LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster)

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster) The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1 Jeeves in the offing jaw-12

Jeeves in the offing jaw-12