- Home

- P. G. Wodehouse

Wodehouse On Crime

Wodehouse On Crime Read online

WODEHOUSE ON CRIME

P. G. WODEHOUSE

EDITED AND WITH A PREFACE BY

D. R. BENSEN

FOREWORD BY ISAAC ASIMOV

TICKNOR & FIELDS

NEW HAVEN AND NEW YORK

1981

* * *

Copyright © 1981 by D. R. Bensen

Foreword copyright © 1981 by Isaac Asimov

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing by the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to Ticknor & Fields, 383 Orange Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06511.

Designed by Sally Harris / Summer Hill Books

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Wodehouse, P. G. (Pelham Grenville), 1881-1975.

Wodehouse on crime.

1. Crime and criminals—Fiction. I. Bensen, D. R.

(Donald R.), 1927- . II. Title.

PR6045.053A6 1981 823’.9i2 81-5697

ISBN 0-89919-044-8 AACR2

Printed in the United States of America s 10 987654321

* * *

“Strychnine in the Soup” copyright © 1932 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1960.

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” copyright © 1937 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1965.

“Ukridge Starts a Bank Account” copyright © 1967 by P. G. Wodehouse.

“The Purity of the Turf’ copyright © 1923 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1951.

“The Smile That Wins” copyright © 1931 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1959.

“The Purification of Rodney Spelvin” copyright © 1927 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1955.

Without the Option copyright © 1927 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1955.

The Romance of a Bulb-Squeezer” copyright © 1928 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1956.

Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” copyright © 1923 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1951.

“The Fiery Wooing of Mordred” copyright © 1936 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1964.

“Ukridge’s Accident Syndicate” copyright © 1926 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1954.

“Indiscretions of Archie” copyright © 1921 by P. G. Wodehouse, renewed 1949.

* * *

Anne

Amor e cor gentile son una cosa

Foreword: THE LOVABLE CRIMINALITY OF P. G. WODEHOUSE

by Isaac Asimov

* * *

P. G. WODEHOUSE, AS WE ALL KNOW, CREATED A world of his own; or, rather, forced one to live past its time. He took Edwardian England, purified it of its grosser elements, and kept it alive by some alchemy, of which only he knew the secret, right into the Vietnam era.

And in doing so, he imbued every aspect with lovability.

Do some of his characters seem like wastrels? Semi-idiots? Excrescences on the face of society?

Undoubtedly, but, one and all, each worthless idler would rather die by torture than sully a woman’s name, however indirectly and involuntarily. All would engage, at a moment’s notice, in any act of chivalry and kindness, though it meant the loss of all their worldly goods (all five pounds of it) or, worse yet, though it meant a rip in their perfectly-creased trousers.

It is because of my admiration for these deadbeats that I have had an ambition that has plagued me steadily for forty years. I want to dine at the Drones Club.

It’s no use telling me there’s no such organization. Somewhere, in some magic place in London, I know it must exist and oh to be there, in April or any other month.

In moments of high spirits, Wodehouse tells us, the gilded lordlings of the Drones Club cannot control their exuberance, and “a goodish bit of bread is thrown about.” I want to be there and throw bread. I want to bean someone with a crusty roll.

Think how lovable a world must be where throwing a crusty roll in a private club is what high spirits lead to. Consider Frederick Altamont Cornwallis Twistleton, Earl of Ickenham.

With reference to him, a Drone has more than once remarked: “I don’t know if you know what is meant by the word ‘excesses' but that is invariably what Lord Ickenham commits when he finds himself in London.”

And what are these excesses? Why, typically they consist of impersonating some bounder in order that the kindly Ickenham might help a damsel in distress.

To be sure Lord Ickenham, Galahad Threepwood, and several others are constantly being thrown out of nightclubs, but the reason for it is never described. I suspect it is because they throw crusty rolls at a headwaiter who well deserves it.

There are outright villains in Wodehouse’s accounts who are mean, self-centered and penny-pinching, such as H. C. Purkiss, who is Bingo Little’s boss, or Ivor Llewellyn, that quintessence of Hollywood magnatehood; but these are usually so plagued by indigestion, high blood pressure, and ferocious wives that one is satisfied at once that they are adequately punished each day for anything they do.

It is admittedly hard to love Oofy Prosser, the Drones Club millionaire, but he can be forgiven for the sake of his case of terminal acne. It is even more difficult to love Percy Pilbeam, the well-known private detective, but to possess a face which, under all disguises, inspires unanimous mistrust is punishment enough.

This book you have in your hand, however, deals with a special subdivision of Wodehousian activity — that of crime.

Can there be crime in the never-never-land of P. G. W. idyllatry?

Certainly! The tales are saturated with it, and even that does not weaken our love.

Consider the misdemeanor of pinching a policeman’s helmet. This is the particular specialty of young Bertram Wooster, the most lovable of all Wodehouse’s characters and one who combines a negligible intelligence with an absolutely perfect ability to tell a complicated story. (Since I am so much more intelligent than Bertie, why is my ability at telling a complicated story somewhat less than perfect? I suppose that that is one of those cosmic questions which could be answered even by Einstein only with a thoughtful, “er … ah… .”)

To be sure, the helmet-pinching almost always takes place on the occasion of Boat Race Night which, I take it, is the time when Oxford and Cambridge engage in some obscure contest. Apparently, all the graduates of either school (and all Wodehouse wastrels have passed through Oxford untouched by human thought) are honor-bound to get tipsy, whether they want to or not.

Then, too, the mildness of the crime is accentuated by the fact that no one in his right mind cares if a Wodehouse policeman or constable (routinely fat, obtuse and intent on laying siege to the hearts of innocent housemaids) is rendered helmetless.

Finally, the act is sometimes inspired by the righteous sense of retaliation of some fiery young woman (Stephanie Byng and Roberta Wickham spring instantly to mind) who long to bring the gray hairs of a particular constable with sorrow to the grave — after that constable, for instance, has cited the dog Bartholomew for chewing thoughtfully on the ankle of said constable with teeth that bite like the serpent and sting like the adder. Under these circumstances, the fiery young woman qualifies as a damsel in distress, and by the Wodehousian code all must rally to her defense.

There are, however, worse crimes. You can’t throw a rock anywhere in Wodehouse without hitting someone who is pinching silver cow creamers or prize pigs. These are valuable things, and their theft qualifies as grand larceny. Long prison sentences are in order if the malefactor is caught.

But consider the motives. It is always made abundantly clear that Sir Watkyn Bassett has no right to a cow creamer. In the first place, it has been obtained dubiously, and in the second place, his cha

racter disqualifies him. Bertie’s aunt. Dahlia Travers (the good and deserving aunt) would argue that point at the top of her voice, if you asked her — or if you did not — salting it with a ripe fox-hunting expletive (never specified) that you could hear in the next county.

Again, the prize pig, when stolen, is usually stolen in order to stiffen the cooked-spaghetti spine of Clarence, Lord Emsworth, so that he might withstand the haughty stare of his sister. Lady Constance (the daughter of a hundred Earls) and come to the aid of a damsel in distress.

More awe-inspiring are the crimes against the code of the gentleman.

It is taken for granted that any gentleman would cheat any tradesman, and do so without a second’s remorse. After all, tradesmen are created only so that they might be cheated by their betters.

However, no gentleman would dream of backing down on a debt of honor to a fellow gentleman. You might cheat a bounder, in other words, but never a fellow cheater.

There are reasons for that. If a bookie catches you cheating, the very worst that can happen is that some large bruiser (usually named Horace — a simple-minded soul with a one-word vocabulary: “R”) will scoop out your insides with his bare hands. Cheating a gentleman, however, will cause you to be asked to resign your club.

Consequently, many of Wodehouse’s accounts deal with the nobbling of contestants in important sporting events such as the egg-in-the-spoon race or the choirboys’ open (to which all can enter whose voices have not yet broken as of Lammastide last). And I need not mention the vile actions taken in connection with the Great Sermon Handicap.

In fact, when one stops to think of it, there is rarely a story in the entire Wodehouse opera which doesn’t feature crime.

In this one, Stanley Featherstone Ukridge labors to cheat an honest, hardworking insurance company by the arranging of fraudulent accidents. In that one, Jno. Horatio Biggs kidnaps his victim and feeds him bread and water to enforce his vile demands. Over there. Sir Murgatroyd Sprockett-Sprockett is plotting arson for the sake of insurance.

Unfortunately, very few of these criminals receive their comeuppance. To be sure, their plots often fail, but virtually never, whether their plots fail or succeed, do they feel the large hand of a policeman (with or without a helmet) upon a shoulder — let alone being forced to face the baleful glance of a magistrate at the Bosher Street Police Court, or getting two weeks without the option. In most cases, in fact, they reach the end of the story in triumph.

But I said “virtually never.” Every once in a while, the prime Wodehousian crime of pinching a policeman’s helmet gets its punishment. Indeed, there is no record of Bertie Wooster actually carrying through the crime successfully. There he is, up before the steely stare of Sir Watkyn Bassett, magistrate (who laid the foundations of his ample fortune — including his cow creamer — by hanging on to the five-pound fines he assesses like glue, for, as Bertie astutely observes, five pounds here and five pounds there mount up). In that case, Bertie has to pay the five pounds out of his ample fortune, even though, as he hotly remarks, a wiser magistrate would have been content with a simple reprimand.

To be sure, on one occasion, Oliver Randolph Sipperley is forced to go to jail — actually spend time in the chokey, old horse — but that is the exception that emphasizes the rule.

But read this collection — and see for yourself.

PREFACE

AS DR. ASIMOV’S INTRODUCTION SUGGESTS, IT would be impossible to present a full collection of those of P. G. Wodehouse’s stories which are concerned with crime. It would be a book of thousands of pages, with a spine about two and a half feet wide, which would make for awkward reading. Almost any short story or novel selected at random will turn out to involve an offense, misdemeanor or felony, as an important part of the plot; and this is to say nothing (which indeed Dr. Asimov does) of professional criminals such as Soapy and Dolly Molloy, Fanny Welch in The Small Bachelor^ Aileen Peavey in Leave It to Psmith, and the several American gangs in Laughing Gas, The Little Nugget and Psmith, Journalist, among others.

Asimov, as befits a trained scientist venturing into a new area, contents himself with describing his observations of a phenomenon, and does not attempt to account for it. An editor is allowed, and expected to take, more leeway; and I propose here to go into the question of why this amiable and blameless man chose to steep his works in crime.

My notion is that, fittingly enough for one of the most professional writers of this century, the two main influences were, one directly and one indirectly, literary.

The direct influence is surely that of Conan Doyle. Wodehouse’s letters tell us that as a youth he used to wait in ill-concealed agitation for the next Strand containing a Sherlock Holmes story. Now consider Holmes. “Consulting detective,” indeed! The man solved crimes, true; but he also committed them with a good deal more flair than his adversaries. “A Scandal in Bohemia” shows him performing quasi-arson and burglary; and blackmail, assault, and abetting of theft, suicide, and even murder do not cause him to turn a hair. And certainly a man who deliberately urges Dr. Watson to provide himself with a loaded firearm must be considered to be criminally reckless. The effect of the Holmes stories must then be seen as strongly baleful.

The second — the indirect — influence is that of Dr. Thomas Arnold who was, if not the actual inventor, the chief propagandist, of the English public-school system. Something over half a century after he flourished, one of the many offshoots of his ideas was Dulwich College, which Wodehouse attended. These institutions, ostensibly intended to provide military, political, academic, commercial and clerical leaders for the late-Victorian Empire, were in fact remarkably similar to well-run minimum-security prisons of the present day and afforded their inmates a sound education in guerrilla warfare on authority and in circumvention of any and all rules. (On reflection, one might say that any contradiction between the stated aim and the result may be illusory.)

The youthful Wodehouse, his mind inflamed by Sherlock Holmes’s high-handed ways with the law, was thrust into a hotbed of iniquity, Dulwich, at which nothing was thought of clandestine visits to the tuck-shop (to U.S. readers, candy store or soda fountain), evasion of boundary restrictions, subversion and terrorism (within the scope afforded by the school), and even midnight feasts of sausages toasted on a pen nib over a candle. Anything goes, if you can get away with it, was the public-schoolboy’s motto.

No one exposed from his tenderest years to these malign forces could expect to escape them entirely. It is to Wodehouse’s credit that, though proceeding directly from Dulwich to employment in a London bank, he did not use his honed criminal skills to become an embezzler or a loan officer, let alone to seek wider employment for them by standing for Parliament or embarking upon a military or mercantile career. One may imagine him, at the turn of the century, asking himself, “Have I got it in me to rake in the big bucks by becoming a Napoleon of Crime? No? Very well, then. I’ll write about it in several score short stories and novels, pausing by the way to toss off a few unforgettable song lyrics — I mean to say, one can be Plum Wodehouse or one can be James Moriarty, and there’s no middle ground, is there?’’

We can only be grateful for the choice he made.

* * *

D. R. Bensen

Croton-on-Hudson, March, 1981

STRYCHNINE IN THE SOUP

FROM THE MOMENT THE DRAUGHT STOUT entered the bar-parlour of the Anglers’ Rest, it had been obvious that he was not his usual cheery self. His face was drawn and twisted, and he sat with bowed head in a distant corner by the window, contributing nothing to the conversation which, with Mr. Mulliner as its centre, was in progress around the fire. From time to time he heaved a hollow sigh.

A sympathetic Lemonade and Angostura, putting down his glass, went across and laid a kindly hand on the sufferer’s shoulder.

“What is it, old man?” he asked. “Lost a friend?”

“Worse,” said the Draught Stout. “A mystery novel. Got half-way through it on the jo

urney down here, and left it in the train.”

“My nephew Cyril, the interior decorator,” said Mr. Mulliner, “once did the very same thing. These mental lapses are not infrequent.”

“And now,” proceeded the Draught Stout, “I’m going to have a sleepless night, wondering who poisoned Sir Geoffrey Tuttle, Bart.”

“That Bart, was poisoned, was he?”

“You never said a truer word. Personally, I think it was the Vicar who did him in. He was known to be interested in strange poisons.”

Mr. Mulliner smiled indulgently.

“It was not the Vicar,” he said. “I happen to have read The Murglow Manor Mystery. The guilty man was the plumber.

“What plumber?”

“The one who comes in chapter two to mend the shower-bath. Sir Geoffrey had wronged his aunt in the year ’96, so he fastened a snake in the nozzle of the shower-bath with glue; and when Sir Geoffrey turned on the stream the hot water melted the glue. This released the snake, which dropped through one of the holes, bit the Baronet in the leg, and disappeared down the waste-pipe.”

“But that can’t be right,” said the Draught Stout. “Between chapter two and the murder there was an interval of several days.”

“The plumber forgot his snake and had to go back for it,” explained Mr. Mulliner. “I trust that this revelation will prove sedative.”

“I feel a new man,” said the Draught Stout. “I’d have lain awake worrying about that murder all night.”

“I suppose you would. My nephew Cyril was just the same. Nothing in this modern life of ours,” said Mr. Mulliner, taking a sip of his hot Scotch and lemon, “is more remarkable than the way in which the mystery novel has gripped the public. Your true enthusiast, deprived of his favourite reading, will stop at nothing in order to get it. He is like a victim of the drug habit when withheld from cocaine. My nephew Cyri — ”

Jill the Reckless

Jill the Reckless Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Uncle Fred in the Springtime Sunset at Blandings

Sunset at Blandings Uneasy Money

Uneasy Money The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion

The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion Right Ho, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves The Intrusion of Jimmy

The Intrusion of Jimmy The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1:

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: Aunts Aren't Gentlemen:

Aunts Aren't Gentlemen: The Luck of the Bodkins

The Luck of the Bodkins The Little Nugget

The Little Nugget Money for Nothing

Money for Nothing Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin Mulliner Nights

Mulliner Nights Blandings Castle and Elsewhere

Blandings Castle and Elsewhere Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens Carry On, Jeeves!

Carry On, Jeeves! The Little Warrior

The Little Warrior Ice in the Bedroom

Ice in the Bedroom Leave It to Psmith

Leave It to Psmith Thank You, Jeeves:

Thank You, Jeeves: Money in the Bank

Money in the Bank The Man Upstairs and Other Stories

The Man Upstairs and Other Stories Galahad at Blandings

Galahad at Blandings The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5 Uncle Dynamite

Uncle Dynamite Mike at Wrykyn

Mike at Wrykyn Something Fresh

Something Fresh Eggs, Beans and Crumpets

Eggs, Beans and Crumpets The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books)

The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books) Blanding Castle Omnibus

Blanding Castle Omnibus Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology

Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology Mr. Mulliner Speaking

Mr. Mulliner Speaking Hot Water

Hot Water The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves The Mating Season

The Mating Season Meet Mr. Mulliner

Meet Mr. Mulliner The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories

The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel

Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel Young Men in Spats

Young Men in Spats The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4 A Pelican at Blandings:

A Pelican at Blandings: Plum Pie

Plum Pie Wodehouse On Crime

Wodehouse On Crime The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves The Man With Two Left Feet

The Man With Two Left Feet Full Moon:

Full Moon: Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit:

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit: Ring For Jeeves

Ring For Jeeves Something New

Something New The Girl on the Boat

The Girl on the Boat The Girl in Blue

The Girl in Blue Pigs Have Wings:

Pigs Have Wings: The Adventures of Sally

The Adventures of Sally A Prefect's Uncle

A Prefect's Uncle Lord Emsworth and Others

Lord Emsworth and Others Quick Service

Quick Service The Prince and Betty

The Prince and Betty The Gem Collector

The Gem Collector The Gold Bat

The Gold Bat Expecting Jeeves

Expecting Jeeves Doctor Sally

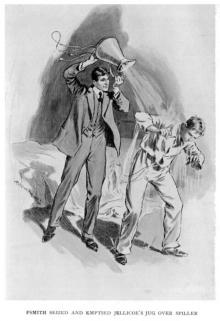

Doctor Sally Psmith, Journalist

Psmith, Journalist The Golf Omnibus

The Golf Omnibus Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather A Damsel in Distress

A Damsel in Distress The Coming of Bill

The Coming of Bill Summer Lightning

Summer Lightning Piccadilly Jim

Piccadilly Jim Psmith in the City

Psmith in the City The Pothunters

The Pothunters Service With a Smile

Service With a Smile Big Money

Big Money Three Men and a Maid

Three Men and a Maid Mike and Psmith

Mike and Psmith Mike

Mike Tales of St. Austin's

Tales of St. Austin's Indiscretions of Archie

Indiscretions of Archie Pigs Have Wings

Pigs Have Wings The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4 The White Feather

The White Feather Luck of the Bodkins

Luck of the Bodkins THE SPRING SUIT

THE SPRING SUIT Full Moon

Full Moon Very Good, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves Thank You, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves Reginald's Record Knock.

Reginald's Record Knock. Wodehouse At the Wicket

Wodehouse At the Wicket LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster)

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster) The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1 Jeeves in the offing jaw-12

Jeeves in the offing jaw-12