- Home

- P. G. Wodehouse

Service With a Smile Page 4

Service With a Smile Read online

Page 4

‘Would you?’

‘Nothing would please me more. When do you return there?’

‘Tomorrow. This is very good of you, Ickenham.’

‘Not at all. We earls must stick together. There is just one thing. You won’t mind if I bring a friend with me? I would not ask you, but he’s just back from Brazil and would be rather lost in London without me.’

‘Brazil? Do people live in Brazil!’

‘Frequently, I believe. This chap has been there some years. He is connected with the Brazil nut industry. I am a little sketchy as to what his actual job is, but I think he’s the fellow who squeezes the nuts in the squeezer, to give them that peculiar shape. I may be wrong, of course. Then I bring him with me?’

‘Certainly, certainly, certainly. Delighted, delighted.’

‘A wise decision on your part. Who knows that he may not help the general composition? He might fall in love with the secretary and marry her and take her to Brazil.’

‘True.’

‘Or murder the Duke with some little-known Asiatic poison. Or be of assistance in a number of other ways. I’m sure you’ll be glad to have him about the place. He is house-broken and eats whatever you’re having yourself. What train are you taking tomorrow?’

‘The 11.45 from Paddington.’

‘Expect us there, my dear Emsworth,’ said Lord Ickenham. ‘And not only there, but with our hair in a braid and, speaking for myself, prepared to be up and doing with a heart for any fate. I’ll go and ring my friend up now and tell him to start packing.’

3

It was some hours later that Pongo Twistleton, having a tissue-restorer before dinner in the Drones Club smoking-room, was informed by the smoking-room waiter that a gentleman was in the hall, asking to see him, and a shadow fell on his tranquil mood. Too often when gentlemen called asking to see members of the Drones Club, their visits had to do with accounts rendered for goods supplied, with the subject of remittances which would oblige cropping up, and he knew that his own affairs were in a state of some disorder.

‘Is he short and stout?’ he asked nervously, remembering that the representative of the Messrs Hicks and Adrian, to whom he owed a princely sum for shirting, socks and under-linen could be so described.

‘Far from it. Tall and beautifully slender,’ said a hearty voice behind him. ‘Svelte may be the word I am groping for.’

‘Oh, hullo, Uncle Fred,’ said Pongo, relieved. ‘I thought you were someone else.’

‘Rest assured that I am not. First, last and all the time yours to command Ickenham! I took the liberty of walking in, my dear Pongo, confident that I would receive a nephew’s welcome. We Ickenhams dislike to wait in halls. It offends our pride. What’s that you’re having? Order me one of the same. I suppose it will harden my arteries but I like them hard. Bill not with you tonight?’

‘No. He had to go to Bottleton East to pick up some things.’

‘You have not seen him recently?’

‘No, I haven’t been back to the flat. Do you want me to give you dinner?’

‘Just what I was about to suggest. It will be your last opportunity for some little time. I’m off to Blandings Castle tomorrow.’

‘You’re… what?’

‘Yes, after I left you I ran into Emsworth and he asked me to drop down there for a few days or possibly longer. He’s having trouble, poor chap.’

‘What’s wrong with him?’

‘Practically everything. He has a new secretary who harries him. The Duke of Dunstable seems to be a fixture on the premises. Lady Constance has pinched his favourite hat. and given it to the deserving poor, and he lives in constant fear of her getting away with his shooting jacket with the holes in the elbows. In addition to which, he is much beset by Church Lads.’

‘Eh?’

‘You see how full my hands will be, if I am to help him. I shall have to devise some means of ridding him of this turbulent secretary —’

‘Church Lads?’

‘— shipping the Duke back to Wiltshire, where he belongs, curbing Connie and putting the fear of God into these Church Lads. An impressive programme, and one that would be beyond the scope of a lesser man. Most fortunately I am not a lesser man.’

‘How do you mean, Church Lads?’

‘Weren’t you ever a Church Lad?’

‘No.’

‘Well, many of the younger generation are: They assemble in gangs in most rural parishes. The Church Lads’ Brigade they call themselves. Connie has allowed them to camp out by the lake.’

‘And Emsworth doesn’t like them?’

‘Nobody could, except their mothers. No, he eyes them askance. They ruin the scenery, poison the air with their uncouth cries, and at the recent school treat, so he tells me, knocked off his top hat with a crusty roll.’

Pongo shook his head censoriously.

‘He shouldn’t have worn a topper at a school treat,’ he said. He was remembering functions of this kind into which he had been lured at one time and another by clergymen’s daughters for whose charms he had fallen. The one at Maiden Eggesford in Somerset, when his great love for Angelica Briscoe, daughter of the Rev P. P. Briscoe, who vetted the souls of the peasantry in that hamlet, had led him to put his head in a sack and allow himself to be prodded with sticks by the younger set, had never been erased from his memory. ‘A topper! Good Lord! Just asking for it!’

‘He acted under duress. He would have preferred to wear a cloth cap, but Connie insisted. You know how persuasive she can be.’

‘She’s a tough baby.’

‘Very tough. Let us hope she takes to Bill Bailey.’.

‘Does what?’

‘Oh, I didn’t tell you, did I? Bill is accompanying me to Blandings.’

‘What!’

‘Yes, Emsworth very kindly included him in his invitation. We’re off tomorrow on the 11.45, singing a gypsy song.’

Horror leaped into Pongo’s eyes. He started violently, and came within an ace of spilling his martini with a spot of lemon peel in it. Fond though he was of his Uncle Fred, he had never wavered in his view that in the interests of young English manhood he ought to be kept on a chain and seldom allowed at large.

‘But my gosh!’

‘Something troubling you?’

‘You can’t … what’s the word … you can’t subject poor old Bill to this frightful ordeal.’

Lord Ickenham’s eyebrows rose.

‘Well, really, Pongo, if you consider it an ordeal for a young man to be in the same house with the girl he loves, you must have less sentiment in you than I had supposed.’

‘Yes, that’s all very well. His ball of fluff will be there, I agree. But what good’s that going to do him when two minutes after his arrival Lady Constance grabs him by the seat of the trousers and heaves him out?’

‘I anticipate no such contingency. You seem to have a very odd idea of the sort of thing that goes on at Blandings Castle, my boy. You appear to look on that refined home as a kind of Bowery saloon with bodies being hurled through the swing doors all the time, and bounced along the sidewalk. Nothing of that nature will occur. We shall be like a great big family. Peace and good will everywhere. Too bad you won’t be with us.

‘I’m all right here, thanks,’ said Pongo with a slight shudder as he recalled some of the high spots of his previous visit to the castle. ‘But I still maintain that when Lady Constance hears the name Bailey —’

‘But she won’t. You don’t suppose a shrewd man like myself would have overlooked a point like that. He’s calling himself Cuthbert Meriwether. I told him to write it down and memorize it.’

‘She’ll find out.’

‘Not a chance. Who’s going to tell her?’

Pongo gave up the struggle. He knew the futility of arguing, and he had just perceived the bright side to the situation — to wit, that after tomorrow more than a hundred miles would separate him from his amiable but hair-bleaching relative. The thought was a very heartening one.

Going by the form book, he took it for granted that ere many suns had set the old buster would be up to some kind of hell which would ultimately stagger civilization and turn the moon to blood, but what mattered was that he would be up to it at Lord Emsworth’s rural seat and not in London. How right, he felt, the author of the well-known hymn had been in saying that peace, perfect peace is to be attained only when loved ones are far away.

‘Let’s go in and have some dinner,’ he said.

Chapter Three

1

One of the things that made Lord Emsworth such a fascinating travelling companion was the fact that shortly after the start of any journey he always fell into a restful sleep. The train bearing him and guests to Market Blandings had glided from the platform of Paddington station, as promised by the railway authorities, whose word is their bond, at 11.45, and at 12.10 he was lying back in his seat with his eyes closed, making little whistling noises punctuated at intervals by an occasional snort. Lord Ickenham, accordingly, was able to talk to the junior member of the party without risk, always to be avoided when there is plotting afoot, of being overheard.

‘Nervous, Bill?’ he said, regarding the Rev Cuthbert sympathetically. He had seemed to notice during the early stages of the journey a tendency on the other’s part to twitch like a galvanized frog and allow a sort of glaze to creep over his eyes.

Bill Bailey breathed deeply.

‘I’m feeling as I did when I tottered up the pulpit steps to deliver my first sermon.’

‘I quite understand. While there is no more admirably educational experience for a young fellow starting out in life than going to stay at a country house under a false name, it does tend to chill the feet to no little extent. Pongo, though he comes from a stout-hearted family, felt just as you do when I took him to Blandings Castle as Sir Roderick Glossop’s nephew Basil. I remember telling him at the time that he reminded me of Hamlet. The same moodiness and irresolution, coupled with a strongly marked disposition to get out of the train and walk back to London. Having become accustomed to this kind of thing myself, so much so that now I don’t think it quite sporting to go to stay with people under my own name, I have lost the cat-on-hot-bricks feeling which I must have had at one time, but I can readily imagine that for a novice an experience of this sort cannot fail to be quite testing. Your sermon was a success, I trust?’

‘Well, they didn’t rush the pulpit.’

‘You are too modest, Bill Bailey. I’ll bet you had them rolling in the aisles and carried out on stretchers. And this visit to Blandings Castle will, I know, prove equally triumphant. You are probably asking yourself what I am hoping to accomplish by it. Nothing actually constructive, but I think it essential for you to keep an eye on this Archibald Gilpin of whom I have heard so much. Pongo tells me he is an artist, and you know how dangerous they are. Watch him closely. Every time he suggests to Myra an after-dinner stroll to the lake to look at the moonlight glimmering on the water — and on the Church Lads’ Brigade too, of course, for, I understand that they are camping out down there — you must join the hikers.’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s the spirit. And the same thing applies to any attempt on his part to get the … popsy is the term you use, is it not?’

‘It is not the term I use. It’s the term Pongo uses, and I’ve had to speak to him about it.’

‘I’m sorry. Any attempt on his part, I should have said, to get the girl you love into the rose garden must be countered with the same firmness and resolution. But I can leave that to you. Tell me, how did you two happen to meet?’

A rugged face like Bill Bailey’s could never really be a mirror of the softer emotions, but something resembling a tender look did come into it. If their host had not at this moment uttered a sudden snort rather like that of Empress of Blandings on beholding linseed meal, Lord Ickenham would have heard him sigh sentimentally.

‘You remember that song, the Limehouse Blues?’

‘It is one I frequently sing in my bath. But aren’t we changing the subject?’

‘No, what I was going to say was that she had heard the song over in America, and she’d read that book Limehouse Nights, and she was curious to see the place. So she sneaked off one afternoon and went there. Well, Limehouse is next door to Bottleton East, where my job was, and I happened to be doing some visiting there for a pal of mine who had sprained an ankle while trying to teach the choir boys to dance the carioca, and I came along just as someone was snatching her bag. So, of course, I biffed the blighter.’

‘Where did they bury the unfortunate man?’

‘Oh, I didn’t biff him much, just enough to make him see how wrong it is to snatch bags.’

‘And then?’

‘Well, one thing led to another, sort of.’

‘I see. And what is she like these days?’

‘You know her?’

‘In her childhood we were quite intimate. She used to call me Uncle Fred. Extraordinarily pretty she was then. Still is, I hope?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s good. So many attractive children lose their grip and go all to pieces in later life.’

‘Yes.’

‘But she didn’t?’

‘No.’

‘Still comely, is she?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you would die for one little rose from her hair?’

‘Yes.’

‘There is no peril, such for instance as having Lady Constance Keeble look squiggle-eyed at you, that you would not face for her sake?’

‘No.’

‘Your conversational method, my dear Bill,’ said Lord Ickenham, regarding him approvingly, ‘impresses me a good deal and has shown me that I must change the set-up as I had envisaged it. I had planned on arrival at the Castle to draw you out on the subject of Brazil, so that you could hold everybody spellbound with your fund of good stories about your adventures there and make yourself the life of the party, but I feel now that that is not the right approach.’

‘Brazil?’

‘Ah, yes, I didn’t mention that to you, did I? I told Emsworth that there was where you came from.’

‘Why Brazil?’

‘Oh, one gets these ideas. But I was saying that I had changed my mind about featuring you as a sparkling raconteur. Having had the pleasure of conversing with you, I see you now as the strong, silent man, the fellow with the far-away look in his eyes who rarely speaks except in monosyllables. So if anybody tries to pump you about Brazil, just grunt. Like our host,’ said Lord Ickenham, indicating Lord Emsworth, who was doing so. ‘A pity in a way of course, for I had a couple of good stories about the Brazilian ants which would have gone down well. As I dare say you know, they go about eating everything in sight, like Empress of Blandings.’

The sound of that honoured name must have penetrated Lord Emsworth’s slumbers, for his eyes opened and he sat up, blinking.

‘Did I hear you say something about the Empress?’

‘I was telling Meriwether here what a superb animal she was, the only pig that has ever won the silver medal in the Fat Pigs class three years in succession at the Shropshire Agricultural Show. Wasn’t I, Meriwether?’

‘Yes.’

‘He says Yes. You must show her to him first thing.’

‘Eh? Oh, of course. Yes, certainly, certainly, certainly,’ said Lord Emsworth, well pleased. ‘You’ll join us, Ickenham?’

‘Not immediately, if you don’t mind. I yield to no one in my appreciation of the Empress, but I feel that on arrival at the old shanty what I shall need first is a refreshing cup of tea.’

‘Tea?’ said Lord Emsworth, as if puzzled by the word. ‘Tea? Oh, tea? Yes, of course, tea. Don’t take it myself, but Connie has it on the terrace every afternoon. She’ll look after you.’

2

Lady Constance was alone at the tea-table when Lord Ickenham reached it. As he approached, she lowered the cucumber sandwich with which she had been about to refresh herself and contrived what

might have passed for a welcoming smile. To say that she was glad to see Lord Ickenham would be overstating the case, and she had already spoken her mind to her brother Clarence with reference to his imbecility in inviting him — with a friend — to Blandings Castle. But, as she had so often had to remind herself when coping with the Duke of Dunstable, she was a hostess, and a hostess must conceal her emotions.

‘So nice to see you again, Lord Ickenham. So glad you were able to come,’ she said, not actually speaking from between clenched teeth, but far from warmly. ‘Will you have some tea, or would you rather … Are you looking for something?’

‘Nothing important,’ said Lord Ickenham, whose eyes had been flitting to and fro as if he felt something to be missing. ‘I had been expecting to see my little friend, Myra Schoonmaker. Doesn’t she take her dish of tea of an afternoon?’

‘Myra went for a walk. You know her?’

‘In her childhood we were quite intimate. Her father was a great friend of mine.’

The rather marked frostiness of Lady Constance’s manner melted somewhat. Nothing would ever make her forget what this man in a single brief visit had done to the cloistral peace of Blandings Castle while spreading sweetness and light there, but to a friend of James Schoonmaker much had to be forgiven. In a voice that was almost cordial she said:

‘Have you seen him lately?’

‘Alas, not for many years. He has this unfortunate habit so many Americans have of living in America.’

Lady Constance sighed. She, too, had deplored this whim of James Schoonmaker’s.

‘And as my dear wife feels rightly or wrongly that it is safer for me not to be exposed to the temptations of New York but to live a quiet rural life at Ickenham Hall, Hants, our paths have parted, much to my regret. I knew him when he was a junior member of one of those Wall Street firms. I suppose he’s a monarch of finance now, rolling in the stuff?’

‘He has been very successful, yes.’

Jill the Reckless

Jill the Reckless Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Uncle Fred in the Springtime Sunset at Blandings

Sunset at Blandings Uneasy Money

Uneasy Money The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion

The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion Right Ho, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves The Intrusion of Jimmy

The Intrusion of Jimmy The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1:

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: Aunts Aren't Gentlemen:

Aunts Aren't Gentlemen: The Luck of the Bodkins

The Luck of the Bodkins The Little Nugget

The Little Nugget Money for Nothing

Money for Nothing Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin Mulliner Nights

Mulliner Nights Blandings Castle and Elsewhere

Blandings Castle and Elsewhere Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens Carry On, Jeeves!

Carry On, Jeeves! The Little Warrior

The Little Warrior Ice in the Bedroom

Ice in the Bedroom Leave It to Psmith

Leave It to Psmith Thank You, Jeeves:

Thank You, Jeeves: Money in the Bank

Money in the Bank The Man Upstairs and Other Stories

The Man Upstairs and Other Stories Galahad at Blandings

Galahad at Blandings The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5 Uncle Dynamite

Uncle Dynamite Mike at Wrykyn

Mike at Wrykyn Something Fresh

Something Fresh Eggs, Beans and Crumpets

Eggs, Beans and Crumpets The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books)

The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books) Blanding Castle Omnibus

Blanding Castle Omnibus Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology

Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology Mr. Mulliner Speaking

Mr. Mulliner Speaking Hot Water

Hot Water The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves The Mating Season

The Mating Season Meet Mr. Mulliner

Meet Mr. Mulliner The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories

The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel

Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel Young Men in Spats

Young Men in Spats The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4 A Pelican at Blandings:

A Pelican at Blandings: Plum Pie

Plum Pie Wodehouse On Crime

Wodehouse On Crime The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves The Man With Two Left Feet

The Man With Two Left Feet Full Moon:

Full Moon: Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit:

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit: Ring For Jeeves

Ring For Jeeves Something New

Something New The Girl on the Boat

The Girl on the Boat The Girl in Blue

The Girl in Blue Pigs Have Wings:

Pigs Have Wings: The Adventures of Sally

The Adventures of Sally A Prefect's Uncle

A Prefect's Uncle Lord Emsworth and Others

Lord Emsworth and Others Quick Service

Quick Service The Prince and Betty

The Prince and Betty The Gem Collector

The Gem Collector The Gold Bat

The Gold Bat Expecting Jeeves

Expecting Jeeves Doctor Sally

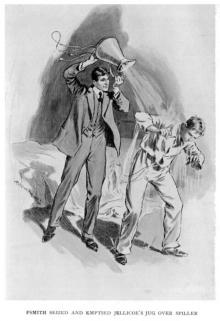

Doctor Sally Psmith, Journalist

Psmith, Journalist The Golf Omnibus

The Golf Omnibus Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather A Damsel in Distress

A Damsel in Distress The Coming of Bill

The Coming of Bill Summer Lightning

Summer Lightning Piccadilly Jim

Piccadilly Jim Psmith in the City

Psmith in the City The Pothunters

The Pothunters Service With a Smile

Service With a Smile Big Money

Big Money Three Men and a Maid

Three Men and a Maid Mike and Psmith

Mike and Psmith Mike

Mike Tales of St. Austin's

Tales of St. Austin's Indiscretions of Archie

Indiscretions of Archie Pigs Have Wings

Pigs Have Wings The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4 The White Feather

The White Feather Luck of the Bodkins

Luck of the Bodkins THE SPRING SUIT

THE SPRING SUIT Full Moon

Full Moon Very Good, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves Thank You, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves Reginald's Record Knock.

Reginald's Record Knock. Wodehouse At the Wicket

Wodehouse At the Wicket LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster)

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster) The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1 Jeeves in the offing jaw-12

Jeeves in the offing jaw-12