- Home

- P. G. Wodehouse

Blanding Castle Omnibus Page 2

Blanding Castle Omnibus Read online

Page 2

Etiquette is not rigid in Arundell Street; but, nevertheless, a girl in a first-floor front may be excused for showing surprise and hesitation when invited to a confidential chat with a second-floor front young man whom she has known only five minutes. But there is a freemasonry among those who live in large cities on small earnings.

“Shall we introduce ourselves?” said Ashe. “Or did Mrs. Bell tell you my name? By the way, you have not been here long, have you?”

“I took my room day before yesterday. But your name, if you are the author of Gridley Quayle, is Felix Clovelly, isn’t it?”

“Good heavens, no! Surely you don’t think anyone’s name could really be Felix Clovelly? That is only the cloak under which I hide my shame. My real name is Marson—Ashe Marson. And yours?”

“Valentine—Joan Valentine.”

“Will you tell me the story of your life, or shall I tell mine first?”

“I don’t know that I have any particular story. I am an American.”

“Not American!”

“Why not?”

“Because it is too extraordinary, too much like a Gridley Quayle coincidence. I am an American!”

“Well, so are a good many other people.”

“You miss the point. We are not only fellow serfs—we are fellow exiles. You can’t round the thing off by telling me you were born in Hayling, Massachusetts, I suppose?”

“I was born in New York.”

“Surely not! I didn’t know anybody was.”

“Why Hayling, Massachusetts?”

“That was where I was born.”

“I’m afraid I never heard of it.”

“Strange. I know your home town quite well. But I have not yet made my birthplace famous; in fact, I doubt whether I ever shall. I am beginning to realize that I am one of the failures.”

“How old are you?”

“Twenty-six.”

“You are only twenty-six and you call yourself a failure? I think that is a shameful thing to say.”

“What would you call a man of twenty-six whose only means of making a living was the writing of Gridley Quayle stories—an empire builder?”

“How do you know it’s your only means of making a living? Why don’t you try something new?”

“Such as?”

“How should I know? Anything that comes along. Good gracious, Mr. Marson; here you are in the biggest city in the world, with chances for adventure simply shrieking to you on every side.”

“I must be deaf. The only thing I have heard shrieking to me on every side has been Mrs. Bell—for the week’s rent.”

“Read the papers. Read the advertisement columns. I’m sure you will find something sooner or later. Don’t get into a groove. Be an adventurer. Snatch at the next chance, whatever it is.”

Ashe nodded.

“Continue,” he said. “Proceed. You are stimulating me.”

“But why should you want a girl like me to stimulate you? Surely London is enough to do it without my help? You can always find something new, surely? Listen, Mr. Marson. I was thrown on my own resources about five years ago—never mind how. Since then I have worked in a shop, done typewriting, been on the stage, had a position as governess, been a lady’s maid—”

“A what! A lady’s maid?”

“Why not? It was all experience; and I can assure you I would much rather be a lady’s maid than a governess.”

“I think I know what you mean. I was a private tutor once. I suppose a governess is the female equivalent. I have often wondered what General Sherman would have said about private tutoring if he expressed himself so breezily about mere war. Was it fun being a lady’s maid?”

“It was pretty good fun; and it gave me an opportunity of studying the aristocracy in its native haunts, which has made me the Gossip’s established authority on dukes and earls.”

Ashe drew a deep breath—not a scientific deep breath, but one of admiration.

“You are perfectly splendid!”

“Splendid?”

“I mean, you have such pluck.”

“Oh, well; I keep on trying. I’m twenty-three and I haven’t achieved anything much yet; but I certainly don’t feel like sitting back and calling myself a failure.”

Ashe made a grimace.

“All right,” he said. “I’ve got it.”

“I meant you to,” said Joan placidly. “I hope I haven’t bored you with my autobiography, Mr. Marson. I’m not setting myself up as a shining example; but I do like action and hate stagnation.”

“You are absolutely wonderful!” said Ashe. “You are a human correspondence course in efficiency, one of the ones you see advertised in the back pages of the magazines, beginning, ‘Young man, are you earning enough?’ with a picture showing the dead beat gazing wistfully at the boss’ chair. You would galvanize a jellyfish.”

“If I have really stimulated you—”

“I think that was another slam,” said Ashe pensively. “Well, I deserve it. Yes, you have stimulated me. I feel like a new man. It’s queer that you should have come to me right on top of everything else. I don’t remember when I have felt so restless and discontented as this morning.”

“It’s the Spring.”

“I suppose it is. I feel like doing something big and adventurous.”

“Well, do it then. You have a Morning Post on the table. Have you read it yet?”

“I glanced at it.”

“But you haven’t read the advertisement pages? Read them. They may contain just the opening you want.”

“Well, I’ll do it; but my experience of advertisement pages is that they are monopolized by philanthropists who want to lend you any sum from ten to a hundred thousand pounds on your note of hand only. However, I will scan them.”

Joan rose and held out her hand.

“Good-by, Mr. Marson. You’ve got your detective story to write, and I have to think out something with a duke in it by to-night; so I must be going.” She smiled. “We have traveled a good way from the point where we started, but I may as well go back to it before I leave you. I’m sorry I laughed at you this morning.”

Ashe clasped her hand in a fervent grip.

“I’m not. Come and laugh at me whenever you feel like it. I like being laughed at. Why, when I started my morning exercises, half of London used to come and roll about the sidewalks in convulsions. I’m not an attraction any longer and it makes me feel lonesome. There are twenty-nine of those Larsen Exercises and you saw only part of the first. You have done so much for me that if I can be of any use to you, in helping you to greet the day with a smile, I shall be only too proud. Exercise Six is a sure-fire mirth-provoker; I’ll start with it to-morrow morning. I can also recommend Exercise Eleven—a scream! Don’t miss it.”

“Very well. Well, good-by for the present.”

“Good-by.”

She was gone; and Ashe, thrilling with new emotions, stared at the door which had closed behind her. He felt as though he had been wakened from sleep by a powerful electric shock.

Close beside the sheet of paper on which he had inscribed the now luminous and suggestive title of his new Gridley Quayle story lay the Morning Post, the advertisement columns of which he had promised her to explore. The least he could do was to begin at once.

His spirits sank as he did so. It was the same old game. A Mr. Brian MacNeill, though doing no business with minors, was willing—even anxious—to part with his vast fortune to anyone over the age of twenty-one whose means happened to be a trifle straitened. This good man required no security whatever; nor did his rivals in generosity, the Messrs. Angus Bruce, Duncan Macfarlane, Wallace Mackintosh and Donald MacNab. They, too, showed a curious distaste for dealing with minors; but anyone of maturer years could simply come round to the office and help himself.

Ashe threw the paper down wearily. He had known all along that it was no good. Romance was dead and the unexpected no longer happened. He picked up his pen and began to write ”The Adventur

e of the Wand of Death.”

CHAPTER II

In a bedroom on the fourth floor of the Hotel Guelph in Piccadilly, the Honorable Frederick Threepwood sat in bed, with his knees drawn up to his chin, and glared at the day with the glare of mental anguish. He had very little mind, but what he had was suffering.

He had just remembered. It is like that in this life. You wake up, feeling as fit as a fiddle; you look at the window and see the sun, and thank Heaven for a fine day; you begin to plan a perfectly corking luncheon party with some of the chappies you met last night at the National Sporting Club; and then—you remember.

“Oh, dash it!” said the Honorable Freddie. And after a moment’s pause: “And I was feeling so dashed happy!”

For the space of some minutes he remained plunged in sad meditation; then, picking up the telephone from the table at his side, he asked for a number.

“Hello!”

“Hello!” responded a rich voice at the other end of the wire.

“Oh, I say! Is that you, Dickie?”

“Who is that?”

“This is Freddie Threepwood. I say, Dickie, old top, I want to see you about something devilish important. Will you be in at twelve?”

“Certainly. What’s the trouble?”

“I can’t explain over the wire; but it’s deuced serious.”

“Very well. By the way, Freddie, congratulations on the engagement.”

“Thanks, old man. Thanks very much, and so on—but you won’t forget to be in at twelve, will you? Good-by.”

He replaced the receiver quickly and sprang out of bed, for he had heard the door handle turn. When the door opened he was giving a correct representation of a young man wasting no time in beginning his toilet for the day.

An elderly, thin-faced, bald-headed, amiably vacant man entered. He regarded the Honorable Freddie with a certain disfavor.

“Are you only just getting up, Frederick?”

“Hello, gov’nor. Good morning. I shan’t be two ticks now.”

“You should have been out and about two hours ago. The day is glorious.”

“Shan’t be more than a minute, gov’nor, now. Just got to have a tub and then chuck on a few clothes.”

He disappeared into the bathroom. His father, taking a chair, placed the tips of his fingers together and in this attitude remained motionless, a figure of disapproval and suppressed annoyance.

Like many fathers in his rank of life, the Earl of Emsworth had suffered much through that problem which, with the exception of Mr. Lloyd-George, is practically the only fly in the British aristocratic amber—the problem of what to do with the younger sons.

It is useless to try to gloss over the fact—in the aristocratic families of Great Britain the younger son is not required.

Apart, however, from the fact that he was a younger son, and, as such, a nuisance in any case, the honorable Freddie had always annoyed his father in a variety of ways. The Earl of Emsworth was so constituted that no man or thing really had the power to trouble him deeply; but Freddie had come nearer to doing it than anybody else in the world. There had been a consistency, a perseverance, about his irritating performances that had acted on the placid peer as dripping water on a stone. Isolated acts of annoyance would have been powerless to ruffle his calm; but Freddie had been exploding bombs under his nose since he went to Eton.

He had been expelled from Eton for breaking out at night and roaming the streets of Windsor in a false mustache. He had been sent down from Oxford for pouring ink from a second-story window on the junior dean of his college. He had spent two years at an expensive London crammer’s and failed to pass into the army. He had also accumulated an almost record series of racing debts, besides as shady a gang of friends—for the most part vaguely connected with the turf—as any young man of his age ever contrived to collect.

These things try the most placid of parents; and finally Lord Emsworth had put his foot down. It was the only occasion in his life when he had acted with decision, and he did it with the accumulated energy of years. He stopped his son’s allowance, haled him home to Blandings Castle, and kept him there so relentlessly that until the previous night, when they had come up together by an afternoon train, Freddie had not seen London for nearly a year.

Possibly it was the reflection that, whatever his secret troubles, he was at any rate once more in his beloved metropolis that caused Freddie at this point to burst into discordant song. He splashed and warbled simultaneously.

Lord Emsworth’s frown deepened and he began to tap his fingers together irritably. Then his brow cleared and a pleased smile flickered over his face. He, too, had remembered.

What Lord Emsworth remembered was this: Late in the previous autumn the next estate to Blandings had been rented by an American, a Mr. Peters—a man with many millions, chronic dyspepsia, and one fair daughter—Aline. The two families had met. Freddie and Aline had been thrown together; and, only a few days before, the engagement had been announced. And for Lord Emsworth the only flaw in this best of all possible worlds had been removed.

Yes, he was glad Freddie was engaged to be married to Aline Peters. He liked Aline. He liked Mr. Peters. Such was the relief he experienced that he found himself feeling almost affectionate toward Freddie, who emerged from the bathroom at this moment, clad in a pink bathrobe, to find the paternal wrath evaporated, and all, so to speak, right with the world.

Nevertheless, he wasted no time about his dressing. He was always ill at ease in his father’s presence and he wished to be elsewhere with all possible speed. He sprang into his trousers with such energy that he nearly tripped himself up. As he disentangled himself he recollected something that had slipped his memory.

“By the way, gov’nor, I met an old pal of mine last night and asked him down to Blandings this week. That’s all right, isn’t it? He’s a man named Emerson, an American. He knows Aline quite well, he says—has known her since she was a kid.”

“I do not remember any friend of yours named Emerson.”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I met him last night for the first time. But it’s all right. He’s a good chap, don’t you know!—and all that sort of rot.”

Lord Emsworth was feeling too benevolent to raise the objections he certainly would have raised had his mood been less sunny.

“Certainly; let him come if he wishes.”

“Thanks, gov’nor.”

Freddie completed his toilet.

“Doing anything special this morning, gov’nor? I rather thought of getting a bit of breakfast and then strolling round a bit. Have you had breakfast?”

“Two hours ago. I trust that in the course of your strolling you will find time to call at Mr. Peters’ and see Aline. I shall be going there directly after lunch. Mr. Peters wishes to show me his collection of—I think scarabs was the word he used.”

“Oh, I’ll look in all right! Don’t you worry! Or if I don’t I’ll call the old boy up on the phone and pass the time of day. Well, I rather think I’ll be popping off and getting that bit of breakfast—what?”

Several comments on this speech suggested themselves to Lord Emsworth. In the first place, he did not approve of Freddie’s allusion to one of America’s merchant princes as “the old boy.” Second, his son’s attitude did not strike him as the ideal attitude of a young man toward his betrothed. There seemed to be a lack of warmth. But, he reflected, possibly this was simply another manifestation of the modern spirit; and in any case it was not worth bothering about; so he offered no criticism.

Presently, Freddie having given his shoes a flick with a silk handkerchief and thrust the latter carefully up his sleeve, they passed out and down into the main lobby of the hotel, where they parted—Freddie to his bit of breakfast; his father to potter about the streets and kill time until luncheon. London was always a trial to the Earl of Emsworth. His heart was in the country and the city held no fascinations for him.

* * *

On one of the floors in one of the buildi

ngs in one of the streets that slope precipitously from the Strand to the Thames Embankment, there is a door that would be all the better for a lick of paint, which bears what is perhaps the most modest and unostentatious announcement of its kind in London. The grimy ground-glass displays the words:

R. JONES

Simply that and nothing more. It is rugged in its simplicity. You wonder, as you look at it—if you have time to look at and wonder about these things—who this Jones may be; and what is the business he conducts with such coy reticence.

As a matter of fact, these speculations had passed through suspicious minds at Scotland Yard, which had for some time taken not a little interest in R. Jones. But beyond ascertaining that he bought and sold curios, did a certain amount of bookmaking during the flat-racing season, and had been known to lend money, Scotland Yard did not find out much about Mr. Jones and presently dismissed him from its thoughts.

On the theory, given to the world by William Shakespeare, that it is the lean and hungry-looking men who are dangerous, and that the “fat, sleek-headed men, and such as sleep o’ nights,” are harmless, R. Jones should have been above suspicion. He was infinitely the fattest man in the west-central postal district of London. He was a round ball of a man, who wheezed when he walked upstairs, which was seldom, and shook like jelly if some tactless friend, wishing to attract his attention, tapped him unexpectedly on the shoulder. But this occurred still less frequently than his walking upstairs; for in R. Jones’ circle it was recognized that nothing is a greater breach of etiquette and worse form than to tap people unexpectedly on the shoulder. That, it was felt, should be left to those who are paid by the government to do it.

R. Jones was about fifty years old, gray-haired, of a mauve complexion, jovial among his friends, and perhaps even more jovial with chance acquaintances. It was estimated by envious intimates that his joviality with chance acquaintances, specially with young men of the upper classes, with large purses and small foreheads—was worth hundreds of pounds a year to him. There was something about his comfortable appearance and his jolly manner that irresistibly attracted a certain type of young man. It was his good fortune that this type of young man should be the type financially most worth attracting.

Jill the Reckless

Jill the Reckless Uncle Fred in the Springtime

Uncle Fred in the Springtime Sunset at Blandings

Sunset at Blandings Uneasy Money

Uneasy Money The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion

The Swoop! or, How Clarence Saved England: A Tale of the Great Invasion Right Ho, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves The Intrusion of Jimmy

The Intrusion of Jimmy The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1:

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: Aunts Aren't Gentlemen:

Aunts Aren't Gentlemen: The Luck of the Bodkins

The Luck of the Bodkins The Little Nugget

The Little Nugget Money for Nothing

Money for Nothing Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin Mulliner Nights

Mulliner Nights Blandings Castle and Elsewhere

Blandings Castle and Elsewhere Love Among the Chickens

Love Among the Chickens Carry On, Jeeves!

Carry On, Jeeves! The Little Warrior

The Little Warrior Ice in the Bedroom

Ice in the Bedroom Leave It to Psmith

Leave It to Psmith Thank You, Jeeves:

Thank You, Jeeves: Money in the Bank

Money in the Bank The Man Upstairs and Other Stories

The Man Upstairs and Other Stories Galahad at Blandings

Galahad at Blandings The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 5 Uncle Dynamite

Uncle Dynamite Mike at Wrykyn

Mike at Wrykyn Something Fresh

Something Fresh Eggs, Beans and Crumpets

Eggs, Beans and Crumpets The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books)

The Swoop: How Clarence Saved England (Forgotten Books) Blanding Castle Omnibus

Blanding Castle Omnibus Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology

Wodehouse at the Wicket: A Cricketing Anthology Mr. Mulliner Speaking

Mr. Mulliner Speaking Hot Water

Hot Water The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 3: The Mating Season / Ring for Jeeves / Very Good, Jeeves The Mating Season

The Mating Season Meet Mr. Mulliner

Meet Mr. Mulliner The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories

The Man with Two Left Feet, and Other Stories Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel

Not George Washington — an Autobiographical Novel Young Men in Spats

Young Men in Spats The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 4 A Pelican at Blandings:

A Pelican at Blandings: Plum Pie

Plum Pie Wodehouse On Crime

Wodehouse On Crime The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves

The Jeeves Omnibus Vol. 2: Right Ho, Jeeves / Joy in the Morning / Carry On, Jeeves The Man With Two Left Feet

The Man With Two Left Feet Full Moon:

Full Moon: Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit:

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit: Ring For Jeeves

Ring For Jeeves Something New

Something New The Girl on the Boat

The Girl on the Boat The Girl in Blue

The Girl in Blue Pigs Have Wings:

Pigs Have Wings: The Adventures of Sally

The Adventures of Sally A Prefect's Uncle

A Prefect's Uncle Lord Emsworth and Others

Lord Emsworth and Others Quick Service

Quick Service The Prince and Betty

The Prince and Betty The Gem Collector

The Gem Collector The Gold Bat

The Gold Bat Expecting Jeeves

Expecting Jeeves Doctor Sally

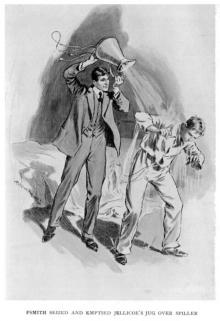

Doctor Sally Psmith, Journalist

Psmith, Journalist The Golf Omnibus

The Golf Omnibus Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather A Damsel in Distress

A Damsel in Distress The Coming of Bill

The Coming of Bill Summer Lightning

Summer Lightning Piccadilly Jim

Piccadilly Jim Psmith in the City

Psmith in the City The Pothunters

The Pothunters Service With a Smile

Service With a Smile Big Money

Big Money Three Men and a Maid

Three Men and a Maid Mike and Psmith

Mike and Psmith Mike

Mike Tales of St. Austin's

Tales of St. Austin's Indiscretions of Archie

Indiscretions of Archie Pigs Have Wings

Pigs Have Wings The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 4: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.4 The White Feather

The White Feather Luck of the Bodkins

Luck of the Bodkins THE SPRING SUIT

THE SPRING SUIT Full Moon

Full Moon Very Good, Jeeves

Very Good, Jeeves Thank You, Jeeves

Thank You, Jeeves Reginald's Record Knock.

Reginald's Record Knock. Wodehouse At the Wicket

Wodehouse At the Wicket LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN V. PLAYERS The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster)

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 5: (Jeeves & Wooster) The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1

The Jeeves Omnibus - Vol 1: (Jeeves & Wooster): No.1 Jeeves in the offing jaw-12

Jeeves in the offing jaw-12